The extent of my thinking about facial hair has — till now — been limited to whether I notice it or not. All along, I’ve limited it to an antithesis of types. At one end, there’s the unkempt chaos I’ll call Civil War Reenactor. On the other end: the waxed curlicues of Hercule Poirot. Between those two extremes, I’ve paid little attention to the infinite ways that men adorn themselves, hirsutely speaking. I’ve lived my life as a beard agnostic.

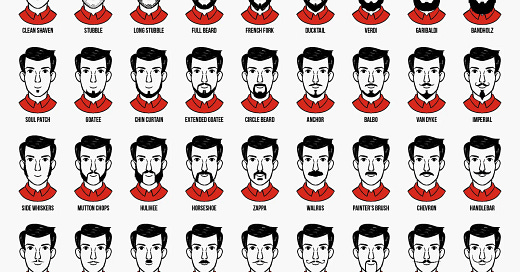

But then this beard reference chart popped up and I realized I’d never heard of a French Fork, or a Bandholz. Not to mention a Hulihee.

Hang on, I thought. Are men deliberately going for specific beard styles? Of course they are! Ashamed at my discovery, I withdrew into my own thoughts. Before this neat guide, I had relegated men’s approach to beards the same way I relegated men’s approach to fashion: just wear something that won’t get you made fun of.

I skimmed a round of recent zeitgeisty reporting about beards (written for tech outlets by, as it were, men with beards). Unsurprisingly, it was uninteresting. But soon enough, I stumbled upon a motherlode of academic research about beards. Next thing I knew, the sun had gone down and I had spent hours and hours reading upwards of 15 scientific studies just about facial hair. And there was so much more. The subject of stubble has been science-i-fied going back to Darwin himself in 1871, and maybe the good ol’ classifier Linnaeus before that (1758). As usual, I am late to the game.

Turns out there are hundreds of millennia of evolutionary biology at play in my personal feelings about beards. So much so that my unconscious — the basis for my instinct as a functioning human — does indeed have strongly held opinions about Mutton Chops. The same goes for everyone. And that includes all humans. This non-neutral, underlying topic is worth scratching your chin over.

The underlying topic, of course, is sexual selection. And it’s a lot more tangled than this barbershop diagram.

“Sexual selection depends not on a struggle for existence, but on a struggle between the males for possession of the females; the result is not death to the unsuccessful competitor, but few or no offspring.” - Charles Darwin, 1859

Like long plumes, and trills, and bright red asses, the seemingly decorative bits are the things that scare off competition. Even poorly groomed whiskers can become intimidating displays of manhood. They’ve been as important to men, historically, as having a Camaro in Seaside Heights is today. That’s approximately what Darwin said, anyway. Moreover, beards are a biological result of what happens after an attractive bit has played a part in possessing enough females for a long enough period of time. Their function is not necessarily to attract females, although that’s nice for the guys in Seaside Heights, their function is to gain an advantage in intra-sexual competition. In other words, beards are for fighting.

Back in the day, I was a carefree graduate student who spent years pondering a painfully esoteric subject: Performance Studies. It’s hard for me (still) to describe it convincingly — maybe because I (still) don’t understand it myself — but basically, it’s a combination of theater and anthropology. My only “job” back then was to research and write about cool stuff (what did I care about paying student loans for decades?). From inside the foggy terrarium of academia, it was endlessly fascinating; far, far from the brutal reality of finding actual, non-esoteric work. Every week, bookish professors and starving performers came through our little program on the 6th floor of NYU’s Tisch building, rhapsodizing about all manner of oddities. One day, we had a visit from one such performer: a performance artist named Jennifer Miller. Jennifer Miller is famous for one thing: she has a beard.

I’m sure Jennifer Miller was fascinating that day. She was a regular at the Coney Island Freak Show (a favorite haunt of mine), and she did some kind of abject circus theater. Intéressante! I looked forward to learning about her, and I told myself to pay attention – numerous times. But I was thrown by the beard. It was oddly full, but more stringy than lumberjack. Her furry embellishment was like nothing I’d ever seen. It matched none of the styles on the nifty table above. It was as if the hair on her head had escaped, expanding into uncharted territory. It crept around under either side of her jaw — not quite conquering her chin. I use the word “crept” knowing that it makes me sound like an asshole. And that’s exactly what I was that day. I told myself again, in no uncertain terms, to be open minded. To be cool. The lady has a beard, so what? Stop being a shithead and listen for once! But when I finally started paying attention to what she was saying, I found myself unconsciously rubbing my own chin as if I had a beard myself.

I pulled my hand away from my face so abruptly that I’m sure she saw me. She also saw that I was bright red with embarrassment. I suppose this was the reaction to the performance she was looking for. Not applause, but recognition.

Jennifer Miller is far from the first woman to let her beard grow in, and certainly not the first person interested in disrupting the normative. She just happens to be the bearded woman that I sat closest to for the longest period of time. Clémentine Delait lived in France in the early 20th Century and, after taking a bet from her husband that she couldn’t do it, grew a lustrous beard. She took that show on the road, too, scaring lions in their cage – so the story goes. She understood the power of performing gender: copious facial hair on a woman’s face freaks people (and lions) out.

Here’s a photo of Madame Delait from 1923:

In my beard-study-reading frenzy, one line startled me more than any other:

“As is the case in other species of great apes, human males perpetrate the vast majority of violence and most of these acts of aggression are directed at other males.” - Beseris, et al

It was simply stated as fact (followed by 10 sources to support it), and it wasn’t even the upshot of the study itself — which presented the findings of an experiment to prove whether or not beards, in fact, protect men’s faces from the impact of hand-to-hand combat, and therefore helped burlier men to survive. Biologically speaking, there is evidence that men have hurt each other so much that they have literally grown bristles out of their cheeks to shield themselves from fractures and lacerations. Also surprising was the fact that modern humans (us) can accurately identify someone who is preternaturally aggressive; we are wired to instinctively understand that a person (man) with a face wider than it is long (facial width-to-height ratio) is a “testosterone-linked trait predictive of reactive aggression, exploitative behavior, cheating, deception, and dominance.” And facial hair is meant to accentuate that width, creating a highly effective “don’t fuck with me” male feature. Point taken! I’ll cross the street now, thank you very much.

Walk past any corporate cubicle, ride any subway, push a cart through the aisles of any big box store and you will see men jutting out their chins, and sporting all the latest grooming styles. It seems innocuous enough; but my once-agnostic self is a fool for believing that was true. The performance of masculinity had always appeared to be a conscious choice to me, one that was as easily legible as a muscle T. If anything, I had always thought that men shaped their stubble to attract the women who liked that kind of thing. Pas moi! But evolutionary science tells us that women have almost nothing to do with it. Beards are for men.

Case in point: this week’s hubbub about Prince William and the newsmaking hair on his face. In this article in the Times (by a writer sporting a fine Long Stubble), every comment is from the manliest of men (including fucktard Trump). All the big dogs have something to say about it. The hurdle that the manprince is trying to clear: perceived manliness. Apparently, he didn’t clear it.

"He’s just putting a strong masculine face forward,” said Dr. Peterkin, who assessed the fledgling beard to be “a wee bit scruffy.”

Since stumbling onto the tuftgraf above, I feel like I’m seeing more beards than ever. And perhaps I am. Apparently, during certain difficult historical periods — and in more crowded, anonymous environments — it’s been proven that “displays of masculinity may be amplified.” Uncertainty = more beards! Of course I always knew that the men in the cubicles, subway, and buying batteries at Costco, were fighting for dominance. But considering the fact that almost 70% of facial fracture ER visits are men, I also know that they need beards to protect their angry, clenching jaws.

The fact is, all of this rabbit-holing about beards has shown me what I already know to be true. On a cellular level, I am aware of the Horseshoe, and the Anchor, and even the Chin Curtain. They are written into human DNA. They aren’t just costumes in a performance of masculinity, but the very expression of manliness itself. An example of a secondary, sexually-selected trait that is (almost) only adapted for men. Jennifer Miller and Clémentine Delait knew the thrill of subverting that truth, and gave a nod to the millions of (all) women who would do anything to keep whiskers from appearing on their faces. But bearded ladies reveal a powerful truth: we tacitly give beards their performative power. We can’t help it. That much seems obvious now. But, as I learned, back in the valuable terrarium of graduate school, not all performances require applause. Just recognition.

Thanks for reading! What’s your feeling about beards? Do you find them intimidating? Laughable? Do tell. xox